What Vince and Rachel Cable have in common…

I started keeping a journal, intermittently, in 1996 – on holiday in Shetland. The first entry is a little watercolour of a beautiful – but dead – baby bird found near a beach. Twenty-five years later, there are nearly as many volumes, mostly written in haste.

As writer Wendy Cope says of her poetry: “I have emotion – no one who knows me could fail to detect it -/But there’s a serious shortage of tranquillity in which to recollect it” (Serious Concerns, 1992).

And so it has been with my prose (mostly prose), none of it written with publication in mind. It was more to “catch the moment”, especially during the events of 2010-2019, when we were near the centre of political life in the UK, and to process my thoughts and feelings at the time rather than unload them onto my nearest and dearest.

As other political spouses know, it’s hard to support one’s partner as well as to find a space to be oneself without inviting critical, often hostile, media attention. No names, no pack drill!

I was a political animal before I was a political wife. As a student in the 1960s, I was a passionate opponent of apartheid and also founded a university society to improve race relations in Britain. As a young wife and mother, I was a teacher and then a translator. In the 1980s, I was a parish councillor whilst running a small beef-rearing enterprise in the New Forest, a role which sparked my interest in affordable rural housing and was my job for the next 20 years. I joined the SDP in 1983 and chaired my local party through the merger with the Liberals after the 1987 election.

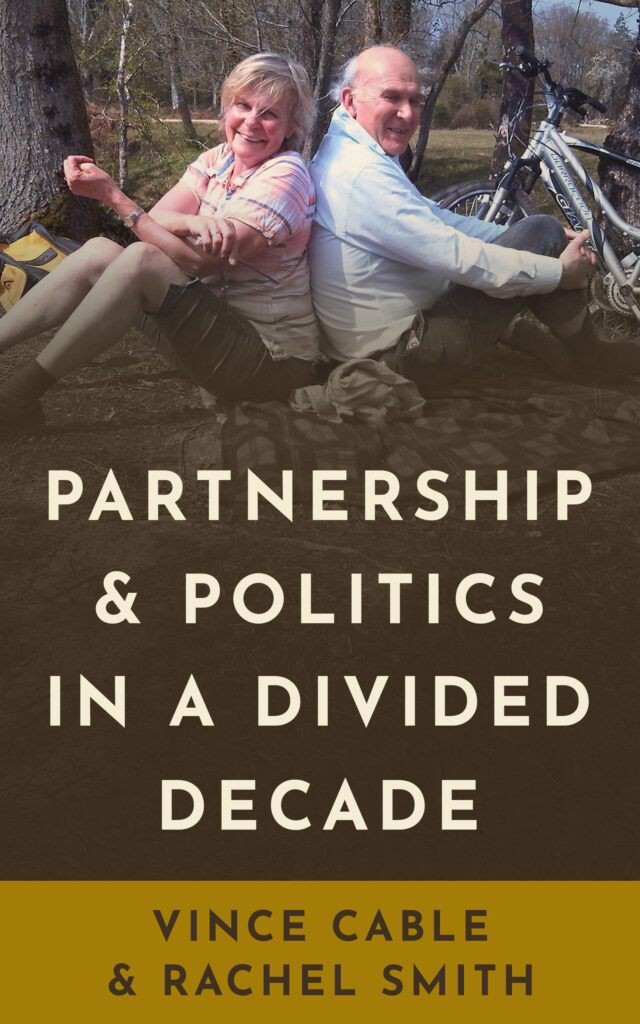

I re-met Vince in 2001, giving a talk about globalisation to the Lymington United Nations Association, with my 85-year-old mother presiding, after a 35-year interval (we had met for about 30 minutes at a charity lunch in Cambridge in 1966). I had been on my own for four years. He says he noticed my “good legs”. I certainly noticed his blue eyes. We had a difference of opinion on home grown dairy products versus free trade and I challenged him to visit my farm.

We married in 2004, and, speaking for myself, have been extremely happy, notwithstanding the pressures of frontline political life.

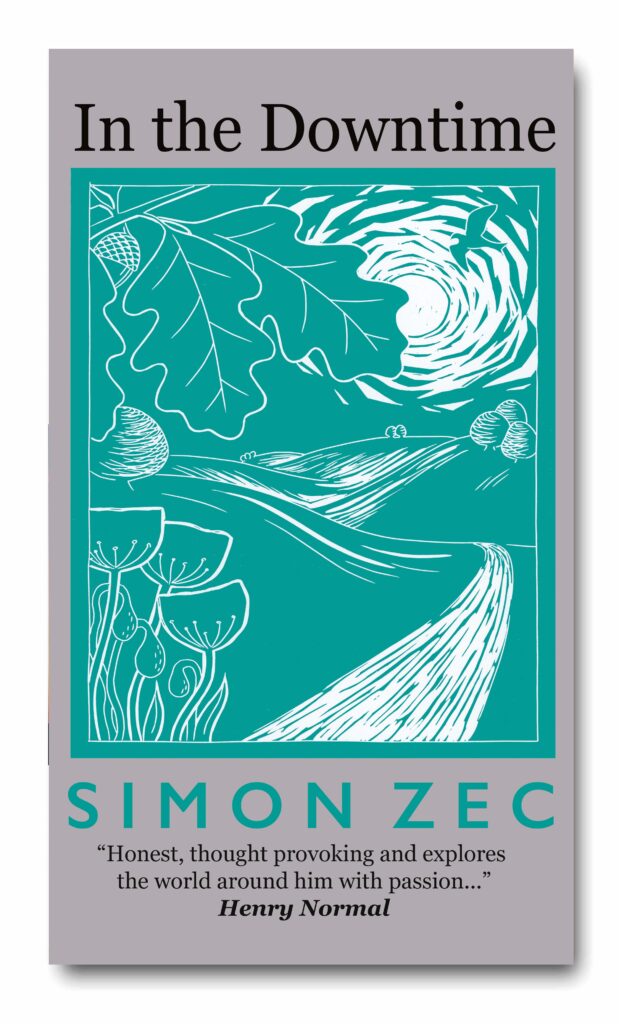

The decade covered in this memoir (Partnership and Politics in a Divided Decade) was one of professional fulfilment for Vince and personal development for me. I managed to keep the strands of my rural, artistic and family life going whilst fully supporting Vince’s high wire political act.

It was only when “the music stopped” because of the pandemic early in 2020 that we found the space and time, if not exactly tranquillity, to write this joint memoir. The narrative is his, the ‘asides’ in italics are mine.

But what we share is the belief that how we are governed matters, and that the coalition was a better period of government than what went before or came after it.

Words of the poem Sometimes by poet and novelist Sheenagh Pugh capture that spirit of high endeavour which characterises politics at its best.

Join us for the formal launch: with the Lib Dem History Group in the National Liberal Club, 1 Whitehall Place, London SW1 on Friday 7 October 2022, at 6.30pm (https://liberalhistory.org.uk/events/ )

You can also hear the authors online at a Radix UK event on 11 October at 6pm:

https://radixuk.org/events/vince-cables-coalition-memoirs/