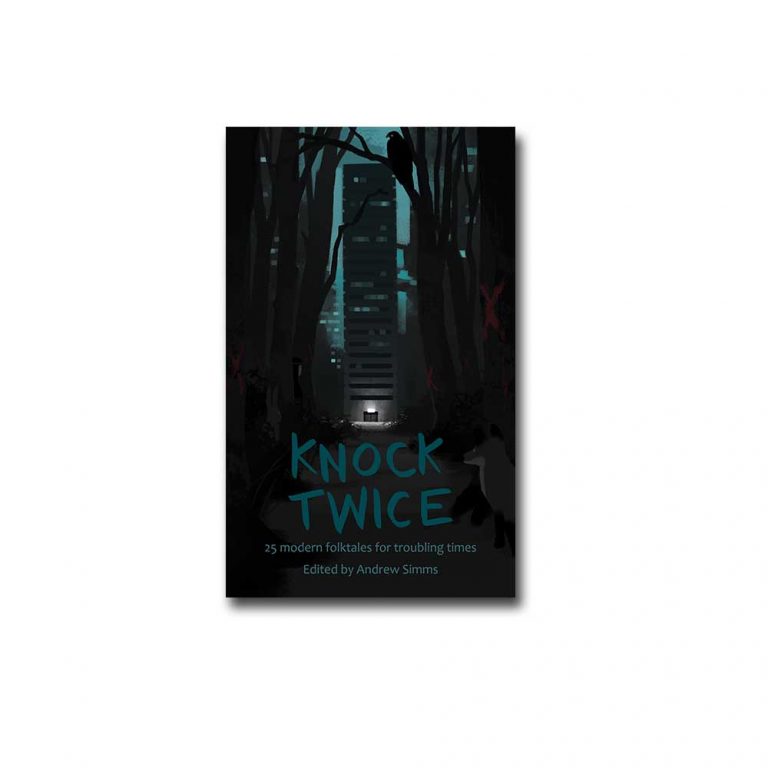

Why would scientists, economists and ecologists replace facts with folk tales?

Andrew Simms, the editor of Knock Twice, writes:

Andrew Simms, the editor of Knock Twice, writes:

‘The last person on earth sat alone in a room, and there was a knock at the door…’ If you want to know what happened next, so do I.

But what about this: ‘the concentration of the greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, in the atmosphere, recently hit 404.19 parts per million.’ Is the curiosity quite the same? Less so, I suspect, even for those who care passionately about our destabilising climate. Stories, more than facts, hold our attention and pattern our lives. Facts we can deny, but stories slip passed our ideological guard into the imagination.

That’s why a group of leading scientists, economists and ecologists recently sat themselves alone in their rooms, put facts momentarily to one side, and wrote modern folk tales for troubling times to convey their issues of concern.

In stories, we make sense of the world, and find ways to deal with what doesn’t make sense. They let us imagine how things can be different, helping them become so. It doesn’t take many words. ‘For sale, baby shoes, never worn,’ has been called the saddest story written. Margaret Atwood’s, ‘Longed for him. Got him. Shit,’ needs no elaboration. And, Eileen Gunn’s six word story: ‘Computer, did we bring batteries? Computer?’ in all its brevity detonates a tension at the heart of human progress. Love allowed in. Demons cast out. Questions raised.

It may be the season of flamboyant, escapist horror, but from manipulative male impresarios exploiting fairy tale ambitions, to overheated hurricanes fuelled, fundamentally, by myths of limitless natural abundance, it seems there are real monsters out there.

Folk tales typically emerge in circumstances of upheaval, enabling us to process and assimilate extreme experience. The irony is that the excesses we wreak on each other through chauvinism and prejudice, or on the non-human world through self-centredness, happen because at some level they are justified by the tales we have told ourselves. That might be to do with apparently innate patterns of power in an industry, or about humanity’s own, unchallengeable power over the natural world. Bad things happen because of the stories we tell that normalise and justify them.

So, if you want change to happen, you have to change deeply embedded cultural narratives. Progressive have learned the hard way in an age of Brexit and Trump that views which resonate with mythologies – such as ‘making America great again’ tapping the former frontier optimism of nation builders, or ‘taking back control’ for the brave, resilient island – are impervious to fact and rational argument.

In both you might also glimpse the village whipped-up by the charismatic trickster who appears in their midst, into a fury of self-destructive suspicion and isolation.

Progressive politics needs better stories as much as it needs facts and policies. Without them, it will flail and flounder. That’s what pushed the group of policy experts to go beyond simply presenting evidence and hoping for the best, to write their own, new compelling tales.

They range from one of the world leading authorities on climate and geo hazards, to one of India’s most prominent and progressive economists, to a leading authority on corporate corruption, the former head of a UK Cabinet Office inquiry, to the head of a UN inquiry into designing a sustainable financial system, and several members from a new generation economic and social activists.

Philip Pullman, the great contemporary storyteller whose new novel is out, like William Blake, is healthily sceptical of institutional religion. But he is evangelical about the importance of stories, which he calls the most ancient and effective ways of making sense of the world that can guide us, as we try to live good lives in a world we seem to be simultaneously destroying.

But Pullman also laments how the devil too often gets all the best lines. That’s why it’s so urgent for progressive voices to practise and experiment with their own, more compelling and convincing stories of how to reimagine the world. We can be led by tales that leave frozen by shadows and insecurity, vulnerable to the pedlars of dark myths, who manipulate us with our own fears.

The technocratic world of politics, whether green, left, liberal or other shade of progressive, feels like it has had an imagination by-pass. Compared to the resurgent right its stories too often seem flat and less able to hold an audience. No one is going to change the world if they can’t hold its attention. For those who are committed to creating a fairer world where everyone can thrive within planetary ecological boundaries, it’s time to tell better tales of what went wrong, and how that better world might come to pass.

Knock twice: 25 modern folk tales for troubling times, was published by the Real Press and the New Weather Institute on All Hallows Eve, October 2017.